From September 2020// reaction essay for NYU Stern/Law School Digital Currency, Blockchain, Future of Finance course with Drew Hinkes and David Yermack

Week 1 Reaction

The course so far has been full of interesting ideas. I’ve referenced the very first lecture’s examination of the various ways to incentivize/disincentive behavior — through laws, architecture, markets, and norms — in multiple conversations with classmates and friends. The considerations of systems design when thinking about blockchains and regulatory regimes have clear parallels to the ways I might go about thinking about systems design at a smaller scale when working as a product manager and UX designer focusing on a software ecosystem.

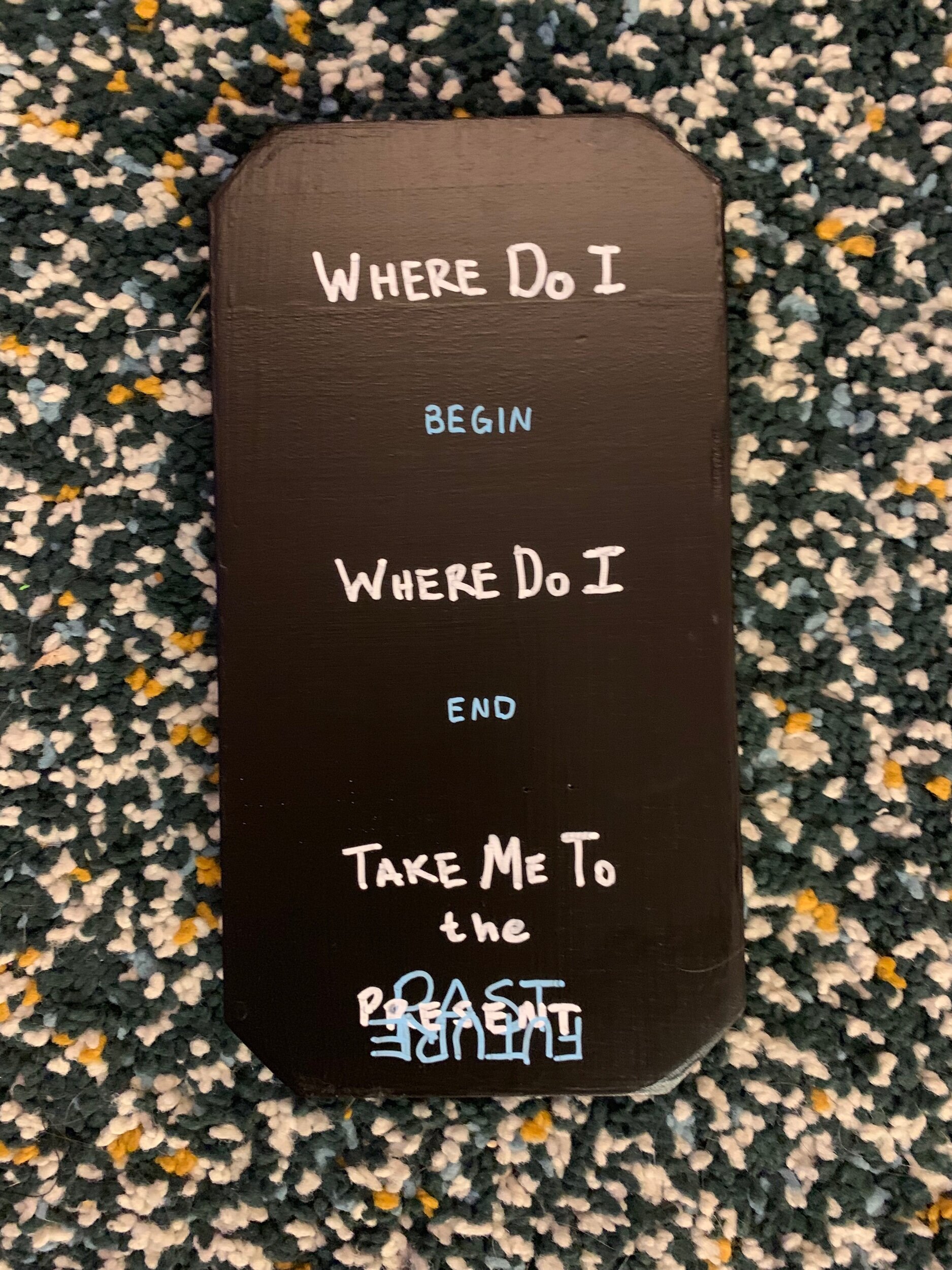

However the topic that I’ve found most thought-provoking, related to both regulation and systems design but distinctly in its own category, is the role of trust in networks. Given that the Bitcoin architecture’s semantics are relatively new to me, I’ll spend the majority of this paper summarizing and illustrating my understanding of trust and Bitcoin’s approach to trustless design, and finish with some thoughts about the implications of this design. I will elaborate on the implications down the line, as I develop a more sophisticated understanding about how the technical architecture could lead to unsuspected behaviors.

A simple exploration of trust

I’ll start by trying to define trust. Trust, I think, requires one actor to become dependent on the actions of another actor, without certainty about whether that 2nd actor’s actions will be consistent with promises or expectations of the nature of their actions. For example, if I pay my apartment’s rent on September 30th in full before charging my roommate for his half, I trust that he will pay me back in a timely manner. Why might I trust him?

Perhaps it’s because he has a track record of paying debts in a timely manner. It could be that his failure to pay back would cause him sufficient tension and risk of harm -- we live in the same space -- that I assume he would not act against his interest. Perhaps he will give me collateral to insure against his non-payment. In all of these cases, I would need to compute the risk of failure to pay and decide whether it was sufficiently small for me to pay the rent in-full.

In this setup, I know my roommate quite well, and the transaction is just between our 2 parties. If he defaults, the trust between us will be broken, and I’ll assume the costs associated with that. What if, instead, I am looking to sublet my apartment to a stranger. How could I ensure that this stranger was able to pay? In order to build trust, perhaps that stranger would be willing to pre-pay the rent. But why would they trust that I wouldn’t run off with the money? Instead we might seek a trusted third party to accept the stranger’s rent payment and pay me upon successful delivery of the apartment.

Why would we trust this third party? Likely for the same reasons that I might trust my roommate -- history of trustworthiness, sufficient risk of harm to themselves upon failure, insurance. A motivated bad actor could exploit any of these; this is at the heart of Satoshi’s whitepaper.

Bitcoin’s approach to trustless network design

The Bitcoin whitepaper clearly identified trusted third parties in financial transactions as an unacceptable risk that could be removed by a system of trustless verification of transactions. Satoshi’s proposal has three key features:

A distributed ledger of timestamped transaction blocks, viewable to anyone

Cryptographic design that links all previous transactions with most recent transactions, leading to an effectively immutable ledger

A system of self-adjusting competitive incentives for verifying transactions that make coordination of false verifications extremely unlikely

Taken together, this system is designed to shift the responsibility of verifying transactions from a trusted third party to the crowd. Its assumption is that the incentives laid out in the system will attract a sufficient number of nodes to do the work of mining coins and verifying transactions to have the scale needed to mitigate the risks of manipulation.

Implications of trustless design

The first question to examine is whether this system is truly “trustless.” It is true that this design no longer requires a single trusted third party. Now, instead, trust is placed in the design itself; that there are sufficient checks to any attempts at sabotage. What are those different types of “attack” that the system designs against?

Satoshi notes in his introduction that “The system is secure as long as honest nodes collectively control more CPU power than any cooperating group of attacker nodes.” If attacker nodes controlled more CPU power than honest nodes, they would be able to coordinate a falsified transaction log of recent transactions, with exponential difficulty in replacing older transactions due to the Merkle Tree hashing structure. The potential for bad actors to accrue this level of power is probably empirically model-able, but in the absence of having done this exercise or researching existing work on the viability of this sort of attack, suffice to say that it would require huge levels of resources and coordination at this point in time to pull this off, and would probably only be able to be done by a “superpower” sovereign nation-state.

With this power, Satoshi argues that “If a greedy attacker is able to assemble more CPU power than all the honest nodes, he would have to choose between using it to defraud people by stealing back his payments, or using it to generate new coins. He ought to find it more profitable to play by the rules, such rules that favour him with more new coins than everyone else combined, than to undermine the system and the validity of his own wealth.”

Satoshi’s reasoning makes sense in the case of an infinite game -- that the interest is in continuing to accrue coins indefinitely.

If the game is deterministic -- that the entity with the most coins at a particular moment in time “wins” -- I believe the incentive to pull off a coordinated attack gets much higher. Using BTC’s blockchain mechanism for voting seems like a case where this type of deterministic system might manifest itself.

During our last class, I asked Scott Stornetta about blockchain voting schemes, and he mentioned that there are a number of compelling use cases already in-flight. I will be researching the existing work done on blockchain voting design to see how folks work around incentives to manipulate the blockchain under deterministic circumstances.